La Guilde des Tramarades

✦

idée de jeu sérieux

pour une économie entre pairs

~ une proposition ~

Introduction : un jeu pour système

D’abord : qu’est-ce, en deux mots, que La Guilde des Tramarades ? Eh bien, imaginez un SimCity qui déborde de votre écran pour englober le monde réel. Un jeu où chacun.e joue son propre rôle, avec l’aide de tous les pouvoirs communicationnels des tramices, nos tableaux de bord intelligents personnels et fidèles compagnons.

*

Notez que le présent texte n’est pas un manuel d’instruction ; pas encore. C’est avant tout une invitation faite aux : concepteurs, designers, modérateurs, philosophes, programmeurs, béta-testeurs, etc. (et à leur imagination stimulée) pour faire exister ensemble une telle idée. C’est une proposition ouverte qui ne prétend pas détenir la solution parfaite, mais qui esquisse les règles d’un jeu — La Guilde des Tramarades — dont nous pourrions, ensemble, faire le laboratoire d’une économie plus juste et plus joyeuse ~ sans doute plus inventive également.

*

Votre téléphone est-il devenu si génial qu’il vous assiste intelligemment dans vos communications ? Parlez-vous à la maison, comme dans les films de vaisseaux spatiaux, à votre ordinateur de bord ? Pas encore ? Et s’il existait un jeu social sérieux de ce type où nous reprendrions, à travers lui, collectivement, individuellement ― et toujours volontairement ― rien de moins que les rênes de notre économie et de nos vies ?

Imaginez une console (tableau de bord) qui ne se contente pas de vous obéir passivement, mais qui vous aide aussi à naviguer dans la complexité du social, à tisser des liens, et à transformer vos aspirations en réalités tangibles. Avec une tramice*, nous visons ce sentiment de pilotage éclairé et de participation optimisée.

* Le mot est une taquine contrepèterie sur le titre d’un célèbre film dystopique de 1999 où la machine n’avait fait des humains qu’une bouchée, ou presque. Mais nous pouvons aussi inverser cette histoire et se l’adjoindre comme assistante, la fine machine. 😉 Et nous mettre à tramer un brin, nous, tramarades sachant tramer !

*

Notre système économique actuel, bien que manifestement enrichissant pour certains, tel qu’il est, centralisé, usuraire et basé sur la dette, montre ses limites à être réellement inclusif. Il échappe à notre contrôle, dévalorise les travaux essentiels, conduit à la pauvreté, menace l’écologie et nos libertés, mène à l’idôlatrie du succès et se nourrit de guerres. ― Heureusement, un système sensé est possible !

La présente Proposition se veut ni plus ni moins que celle d’un tel système économique et social fondé sur la ludification intelligente de la communication interindividuelle. Un système qui s’incarne par un jeu grandeur nature méta-sociétal, La Guilde des Tramarades (ou plus simplement La Guilde), caractérisée par l’emploi de ces deux outils :

- des consoles de jeu d’aventure (appelées tramices) dotées d’assistance artificielle et fonctionnant en réseau ; bien plus que de simples tableaux de bords de réalité en quelque sorte augmentée, ou du moins optimisée : elles sont nos assistantes personnelles qui assurent la bonne communication des souhaits, besoins, offres et projets des utilisateurs, les tramarades ― en les aidant à combler leurs souhaits complémentaires, à organiser des rendez-vous à plusieurs ; c’est aussi une interface dédiée à nous permettre de financer collectivement, en s’adossant sur l’enthousiasme qu’elles-mêmes suscitent, les diverses initiatives d’entreprises émergentes, ainsi qu’à pouvoir en discuter ouvertement, ce qui fait de ce jeu-outil un véritable média social ; votre tramice est votre assistante personnelle, votre interface évolutive et votre ordinateur de bord dans un nouveau paradigme où le social se construit de façon émergente (c’est-à-dire : bottom-up, à partir des individus et de leurs interactions, et ensuite vers des structures plus complexes). Au lieu de liker des posts sans impact, vous investissez votre temps et votre attention dans des entreprises réelles (un café, un fablab, un accompagnement dans les études) et vous pouvez en suivre les résultats dans le temps.

- des Carnets de Reconnaissance, individuels et d’entreprises (ainsi que des Carnets de Missions pour ces dernières), registres faits de bon vieux papier (voir l‘Annexe B : Mais où est donc mon carnet d’or ? pour les détails de ces carnets), où tenir nos comptes personnels et d’entreprises tout en favorisant que les individus puissent rester à l’abri de tout élan centraliste qui prétendrait contrôler chacun de nos échanges.

Au cœur du système bat le HOP (pour une Heure d’Ouvrage par une Personne), unité d’échange indicative qui sert à reconnaître la valeur du temps, validé par la communauté des « tramarades ».

Tramarade ? Oui, le mot fait sourire par son cousinage avec camarade, mais notre Guilde n’a rien d’un parti unique. La Guilde, fondée sur la libre association, la décentralisation et la personnalisation, place les leviers d’influence sociale directement entre les mains des personnes, en temps réel. Placer le mot « tramarade » dans le nom du jeu souligne à quel point l’individu en est l’atome constituant. Et si cela invite du même coup à quelque camaraderie, pourquoi pas ?

Ce que la Guilde n’est pas

La Guilde ne propose pas un plan économique qui prédétermine les résultats, les productions ou les valeurs : elle propose un cadre rythmique et formel — le cycle du HOP et tout le protocole de communication — dont la régularité et la simplicité ont pour but de rendre possible la rencontre et la coordination entre des millions d’intentions et d’actions souveraines. Le contenu de l’économie — quelles entreprises prospèrent, quels services sont valorisés — n’est pas conçu en amont, mais émerge intégralement et de façon imprévisible de cette dynamique collective. En ce sens, la Guilde se veut moins un plan qu’un sol fertile et un rythme partagé pour soutenir l’initiative décentralisée. Cela dit, on peut aussi (et sans doute même le devrait-on) y lancer des fonds de prévision et discuter de nos besoins futurs à prévoir.

La Guilde n’est pas non plus un gouvernement. Elle ne légifère pas, ne possède pas de territoire et ne prétend pas résoudre tous les problèmes de coordination sociale. C’est un outil supplémentaire, volontaire, pour faciliter la coopération économique et sociale dans les interstices et au-delà des systèmes existants, en s’y branchant quand c’est nécessaire, et pour y influer. Pour comprendre comment la Guilde se situe par rapport aux catégories politiques traditionnelles, voir l’analyse sociologique en Annexe C.

*

Cette proposition est accompagnée des annexes suivantes, que vous trouverez ci-dessous :

- Charte éthique de la Guilde des Tramarades – Les engagements fondamentaux pour une coopération libre et féconde.

- Mais où est donc mon carnet d’or ? – Le fonctionnement détaillé des carnets de reconnaissance.

- Analyse sociologique – La Guilde comme tentative de dépassement des clivages traditionnels.

- Tramice721 sur Discord – La plateforme de co-conception du projet.

- Sur l’« adossement » des HOPs – Une monnaie à validation rétrospective.

*

À qui le contrôle ?

Dans la Guilde, le contrôle est décentralisé par design et pas seulement dans nos carnets (voir l’Annexe B), qui sont notre banque portative, souveraine, qui ne peut être gelée, surveillée ou contrôlé par un pouvoir central. Il n’y a pas de banque centrale, pas d’impôt obligatoire, et pas de redistribution forcée. Aussi, la participation est toujours volontaire. La Guilde elle-même ne crée pas et ne gère pas de propriété collective des moyens de production. Elle facilite le financement « social » et la coordination d’entreprises qui restent la propriété de leurs fondateurs ou de leurs employés.

On peut quitter la Guilde à tout moment : on convertira alors ses HOPs restants en biens, services, ou accord de conversion avec d’autres tramarades.

Nos tramices intègrent un système de résolution de conflits :

- D’abord, elles servent autant que possible de médiatrices.

- Au besoin, elles ont recours à nous pour trancher ; elles nous aident à former des jurys composés des sept premier.ère.s tramarades disponibles qu’elles tirent au sort localement et qui ne sont pas en conflit d’intérêt avec le cas en litige.

- Selon le verdict du jury : remboursements exigibles (dont le temps des jurés, reconnu en HOPs), peut-être un avertissement ; au pire, suspension de la Guilde.

Ces mécanismes s’appuient sur une charte éthique commune (voir l’Annexe A) qui définit les engagements minimaux attendus de chaque tramarade pour préserver la confiance collective. Lorsqu’un conflit insoluble émerge (ex : attribution de ressources rares, désaccord éthique), ou via tout signalement de fraude, tout tramarade peut proposer la création d’un « Tribunal Ad Hoc ». Cette Quête, approuvée, reçoit un budget en HOPs pour rémunérer les médiateurs, les experts convoqués et les jurés tirés au sort. La décision finale, transparente et motivée, s’impose aux parties et devient jurisprudence ― du moins nos tramices auront-elles quelque mémoire, notamment de ces jugements.

*

Une entreprise ou un tramarade dont le carnet montre un historique cohérent de reconnaissances, de feedbacks positifs et de missions accomplies gagne un capital de confiance, devise non monétaire fondamentale de la Guilde. La fraude, une fois détectée, peut détruire irrémédiablement cet actif. Toutefois, des périodes probatoires peuvent être déclarées. À méditer.

*

Le jeu-système évolue démocratiquement : toute modification approuvée par 80%* des tramarades au scrutin est adoptée. Le vote est transparent ; on peut ainsi s’inspirer les uns des autres. Les règles ne sont pas éternelles — elles sont le reflet vivant de notre intelligence collective.

* Ce seuil est lui-même modifiable. Il a été placé à cette relativement stricte hauteur initiale par souci de prudence et désir d’y aller par incrémentalité douce. Notez aussi qu’il ne concerne que les modifications au système, pas celles qui appartiennent aux entreprises, lesquelles fixent leurs propres seuils et modalités décisionnels.

En mettant dans les mains des personnes un outil capable de tisser un monde limpide et multicolore qui nous ressemble, nous pouvons faire la plupart des choses bien plus aisément et de façon bien plus juste et amusante que dans le monde du contrôle central.

Un jeu d’aventure

en réalité augmentée

Dans ce jeu d’aventure en réseau (RPG, role playing game, avec inventaire, plans, statistiques, et tout), chacun.e joue son propre rôle dans un univers communicationnel qui correspond aux préoccupations, désirs et aspirations profondes de ses constituants : tous les tramarades. Seulement, contrairement à la plupart des jeux, la possibilité se manifeste qu’en passant moins de temps devant nos écrans, il y ait davantage de possibilité de rencontres en personnes, ou du moins de collaboration entre personnes réelles ― et une économie bel et bien en notre contrôle.

Nos tramices affichent des Quêtes, des cartes interactives, l’état des projets, leurs Missions et progressions. Ce n’est pas une simulation. C’est la réalité, rendue lisible et actionnable, dans un paradigme où l’assistance artificielle, orientée à faciliter des connexions significatives est un deltaplane qui amplifie notre autonomie créatrice . . . et non une béquille qui la remplace.

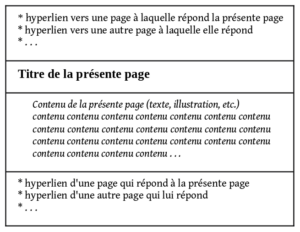

Afin de favoriser l’intelligence collective plutôt que les publicités tapageuses, l’interface doit rester sobre et basée sur l’articulation et la visualisation des idées et de leurs relations. Bien sûr, avec ces facultés augmentées, viennent des responsabilités. ― La liberté est ultimement responsable de tout, même des règles qu’elle se donne.

Tel un mycélium, le réseau facilite la connection d’individus, talents et besoins dans un écosystème vivant où chaque interaction et chaque initiative enrichit l’ensemble.

Imaginez . . . et si le monde émergent de nos mondes était à un nouveau jeu près ?

Miser, entreprendre et participer

Et si, d’abord, nous instaurions un système où nous influons directement sur les investissements faits dans les services que nous voulons voir prospérer ?

L’investissement public,

un SimCity pour le monde réel

Le jeu qui se joue sur une tramice ressemble beaucoup à SimCity, sauf que c’est pour le monde réel, un monde où les tramarades encouragent et reconnaissent les entreprises les un.e.s des autres ― et aussi les idées d’entreprises, à discuter, et peut-être développer et mettre sur pied. La récompense, c’est de voir, par la trame, notre communauté s’épanouir, des équipes se former, et nos carnets se remplir de belles histoires.

Le cycle hebdomadaire

Chaque jeudi à 17:00, chaque tramarade reçoit un budget d’influence, un montant de HOPs équivalent à la somme totale des heures d’ouvrage faites la semaine précédente, dans tout l’univers connecté, celles rémunérées et celles accomplies comme bénévoles, plus 20% (pour permettre la croissance et de parer aux imprévus), divisé par le nombre de tramarades ― autrement dit, chaque tramarade reçoit un budget égal à la moyenne des HOPs créés la semaine précédente, majorée de 20% pour la croissance (paramètre inaugural ajustable démocratiquement). Cette majoration n’est pas cumulative et ne s’applique qu’aux heures d’ouvrage réelles non majorées.

Ce budget d’influence est d’au minimum 5 HOPs et ne peut être de plus de 100 HOPs comme limite supérieure (il n’y a que tant d’heures dans une semaine, et 100 heures, c’est vraiment une grosse semaine).

Ce budget n’est pas un revenu, mais un outil de coordination. Il ne peut être transformé en HOPs échangeables que si l’on contribue activement à une Mission (ou une Quête) que la communauté a choisi de soutenir. De plus, dans l’interface, par design, ce sont les entreprises les plus transparentes qui apparaissent en premier. Elles ont de toute façon avantage à montrer ouvertement leurs progrès et difficultés ; lLa confiance, la crédibilité, est la devise la plus déterminante, dans ce jeu.

Le jeudi à 17:00 est aussi l’heure de tombée pour les entreprises qui veulent annoncer leurs activités prévues, c’est-à-dire leurs Missions ; nombre d’heures d’ouvrage et besoins matériels évalués en HOPs. C’est d’abord sur ces annonces que les tramarades pourront baser leurs réflexions quant aux placements à faire.

Cela me permettrait, par exemple un samedi après-midi, de constater que les besoins de l’entreprise A, que je voulais soutenir, sont déjà comblés, et donc d’investir dans autre chose, quitte à tagguer prioritaire l’entreprise A pour aisément y revenir ensuite.

Afin d’alléger la subtile et potentiellement chronophage tâche (que l’on pourrait qualifier de citoyenne) de miser sa part de soutien ― et en bonne proportion ― sur diverses entreprises, les tramices rendront facile d’automatiser le placement des investissements pour ne pas avoir à tout refaire à chaque semaine.

La période d’investissement se termine le dimanche à minuit. Cela laisse le temps aux tramarades pour explorer les propositions d’entreprises selon leurs propres critères et de débattre d’enjeux avec d’autres tramarades, virtuellement ou en personne, puis pour placer leurs HOPs d’influence dans les diverses entreprises de leur choix. Les HOPs non placés seront répartis automatiquement selon la tendance ― sans toutefois allouer aux entreprises plus qu’elles ne demandent. Pour avoir de l’influence dans le réseau, il suffit de s’appliquer au placement de HOPs, lesquels sont transparents à l’interne (on peut donc s’inspirer les uns des autres), ainsi qu’aux discussions collectives pour apporter le plus de lumière possible.

Il ne s’agit donc pas d’investissement avec retour monétaire ; les seuls dividendes à espérer sont l’existence même ― et la vitalité ― des entreprises que nous désirons voir exister. Ces investissements ne les obligent en rien, mais leur offrent une reconnaissance sociale très tangible.

C’est le moment où les pendules sont remises à l’heure, les montants accordés pour la semaine aux Carnets de Missions finalisés, et aussi l’heure limite pour les entreprises de faire état des heures qui y ont été consacrées, de façon bénévole ou reconnue au carnet.

Les entreprises

« Entreprise », dans ce jeu, est entendu au sens large ; car pourquoi ne pas reconnaître les soins aux jeunes enfants, aux malades, aux personnes dépendantes . . . comme des entreprises légitimes ? Dans la Guilde, une entreprise, c’est aussi bien une start-up qu’une garderie, un potager collectif ou un atelier de réparation. Toute activité qui apporte de la valeur à la communauté a sa place. D’ailleurs, les tramarades eux-mêmes sont considérés comme des acteurs économiques à part entière, et visualisables avec les autres éléments du monde dans la fenêtre Mondo : entreprises, endroits et événements (selon les filtres appliqués ; voir la section Maîtres de nos paramètres et la section suivante : Le plancher commun de la reconnaissance).

Ainsi, le HOP ne mesure pas seulement le temps, mais aussi la reconnaissance de la valeur personnelle universelle en plus de celle, sociale, du travail ; et ce, dans un contexte dûment répertorié. En cela, il résout le paradoxe des sociétés modernes où tant de travaux essentiels (soins, éducation) sont sous-valorisés.

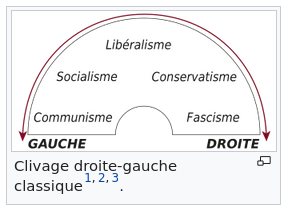

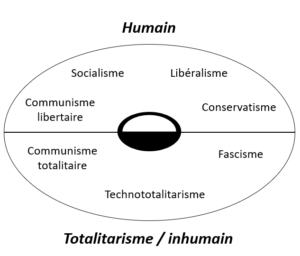

Petite analyse sociologique

Cette approche permet de dépasser un clivage traditionnel. En mettant ainsi ensemble les entreprises payantes et les gratuites, le jeu s’élève au-dessus de la distinction binaire gauche-droite et permet à tous les élans de fleurir et, on l’espère, de porter fruit. Les communs, digitaux et autres, oui, sont fort important dans cette vision, mais les communs comme les privés apparaissent dans la fenêtre Mondo (voir la section À nos tramices !), et c’est à chaque tramarade, et dans les proportions de son choix, de voter (i.e.: investir) en HOPs potentiels pour les uns et les autres.

La Guilde reprend à la gauche la préoccupation de la justice sociale et de la reconnaissance des travaux essentiels, et à la droite le respect de la propriété individuelle et de l’initiative privée. Mais elle les recompose dans un cadre volontaire et décentralisé, où la solidarité n’est pas imposée par l’État mais choisie entre pairs, et où l’économie n’est pas dirigée par un plan central mais émerge de nos interactions libres. En cela, la Guilde est une expérience de démocratie économique radicale, qui vise à réconcilier l’individu et la collectivité.

Cette esquisse d’analyse est approfondie dans l’Annexe C, qui explore les implications sociologiques et philosophiques de la Guilde comme tentative de dépasser les clivages traditionnels.

*

On pourrait craindre que ne se constitue une « classe de politiciens tramiciels », mais, dans ce jeu, on est tous « maires de la City », on est tous politiciens. Chacun.e peut tenter de convaincre les autres, devenir « maire.sse » d’un projet ou d’une idée. Le « pouvoir » n’est qu’une temporaire convergence d’attention, qui se dissout et se reforme ailleurs. Cela transforme la politique en jeu de persuasion continu, où l’autorité est fluide, contextuelle et toujours révocable — exactement comme dans un jeu vidéo où on peut tous être « chef.fe de guilde » un jour et simple membre le lendemain.

*

Récapitulons et précisons : Les projets d’entreprise (les Missions) doivent être présentés avant jeudi 17:00. Les entreprises gagnent à faire des présentations transparentes, bien faire états de leurs avantages et besoins, de les évaluer en HOPs, et à assurer un suivi au long de la semaine via les fils de nouvelles tramiciels, ce qui permet aux tramarades de bien se renseigner avant d’investir ― ou de ré-investir.

Le système repose sur la confiance, la solidarité et l’enthousiasme propagés, non sur des castes administratives. Une entreprise inconnue mais soutenue par des tramarades que vous estimez apparaîtra naturellement dans votre réseau. Nous pourrons ainsi nous influencer les uns les autres.

La légitimité émerge des interactions authentiques. Les projets fictifs ou immatures peineront à gagner cette confiance organique, tandis que les initiatives prometteuses se propageront par le bouche-à-oreille numérique.

*

Dès dimanche à minuit, le budget participatif accordé pour la semaine à chaque entreprise, ce montant de HOPs, visible sur toutes les tramices, est à reporter à la semaine en cours dans le Carnet de Mission des entreprises correspondantes (voir l’Annexe B). Ces carnets leur permettront de reconnaître en HOPs les heures d’ouvrage accomplies selon ― exactement : leur Mission.

Dans ces Carnets de Missions, il n’y a pas de cumul avec des HOPs non utilisés de la période précédente ; s’ils n’ont pas été utilisés par une entreprise durant la période prévue, ces HOPs s’évanouissent dans l’inexistence dont le jeu les avait tirés. Il peut bien sûr y avoir de bonnes raisons, cependant, pour ce non-usage, qu’il reviendra aux entreprises de justifier afin de solliciter une extension.

Une entreprise payante a aussi un ― et possiblement plusieurs ― Carnets de Reconnaissance pour recueillir la pleine reconnaissance de ses œuvres et éventuellement voler de ses propres ailes ― et alors remplir elle-même son Carnet de Mission. Les chiffres d’affaires de ces Carnets de Reconnaissance d’entreprises devront régulièrement être transmis au réseau pour que celui-ci puisse s’autoréguler en connaissance de cause.

Notons que l’investissement dans les entreprises consistant à apprendre des métiers dont la société a besoin est également chose possible et que l’extrême disparité salariale entre un travail spécialisé et un travail non-spécialisé pourrait s’en trouver réduite.

L’interface présentant ces entreprises devra pouvoir les ordonner par les critères et catégories établis par son utilisateur.trice. On peut ici imaginer un système émergent de classification.

Le plancher commun de la reconnaissance

Toutes les personnes demandent des soins et ont des besoins de base à combler, même les plus autonomes. De plus, la force du tout dépend de la vitalité de chaque partie.

C’est pourquoi une allocation universelle modique (AUM) de 5 HOPs par semaine (montant inaugural, universel, inconditionnel et révisable démocratiquement) est versée à chaque tramarade. Simplement parce qu’il faut bien chaque jour, pour pouvoir être apte à faire du bel ouvrage : boire et manger, se vêtir et avoir un endroit où dormir, (etc.), ce qui encourt des coûts. Ces HOPs de soutien sont « étiquetés » et ne peuvent être dépensés que pour certains biens/services agréés essentiels. Les tramarades peuvent aussi déclarer des besoins spécifiques majeurs (handicap, maladie, charge familiale, formation intense) et obtenir validation pour une majoration de leur allocation.

Une fois par an, les tramarades votent pour réévaluer l’AUM en fonction de l’abondance ou de la rareté perçue dans le réseau. C’est la démocratie économique en acte. On pourrait dire que ce modicum, ce filet social symbolique, ces HOPs qui favorisent du même coup l’économie la plus vitale ― sont adossés à la solidarité, à la vie elle-même . . . et vice-versa !

Ce système s’adosse non pas à une dette ou à une matière première, mais à la capacité collective anticipée. Nous faisons le pari que la connaissance fine et en temps réel des besoins et des compétences au sein du réseau est un gage de réalisation plus solide que bien des actifs financiers opaques.

Modalités de la mutualité

On peut placer des HOPs dans une entreprise qui n’est pas la nôtre et ensuite y en gagner par des heures d’ouvrage réelles, mais les heures auto-reconnues ne seront comptabilisées que via tramice, à des fins statistiques et pour déterminer la mise de début de période ― et pas dans les carnets. C’est une façon d’encourager une entreprise doublement : non seulement en y faisant du bénévolat, mais aussi en permettant pendant ce temps de reconnaître l’apport de personnes supplémentaires. Il s’agit aussi d’éviter qu’on s’invente des sinécures autopropulsées.

Ainsi, si deux tramarades (ou davantage) investissent la quasi-totalité de leurs HOPs les uns dans les autres (indice de mutualité de 80% ou plus), cela sera visible sur l’interface et pourra être investigué ― demandera du moins justification. Si les entreprises des partenaires au fond ne font qu’une, ils devront alors formellement faire état de la Mission de leur entreprise commune afin de pouvoir obtenir des HOPs de soutien.

Les Quêtes

et leur reconnaissance rétroactive

Qu’en est-il des besoins qui n’auront pas été prévus ? Il faut quand même les communiquer « en temps réel » et y pourvoir, tout en permettant aux tramarades de placer une part de leur budget d’influence rétroactivement dans les Quêtes accomplies la semaine précédente.

Exemple : Vous consultez votre tramice. Sur la carte, des icônes signalent : une Quête pour pelleter une entrée après une bordée de neige, une autre pour de l’aide aux courses ― besoin urgent. Vous choisissez une Quête et cliquez pour vous porter volontaire. Comme dans un jeu d’aventure, vous choisissez votre mission et intervenez dans le quotidien.

La semaine suivante, cette Quête accomplie est soumise avec les autres entreprises à l’investissement collectif.

Une Quête peut aussi être lancée de façon exclusive au sein d’une entreprise, mais sa reconnaissance passe tout de même par l’investissement public.

Richesse et pudeur

de la transparence

La transparence économique décourage naturellement la fraude. Toutes les entreprises, tous les carnets sont visibles et vérifiables par tous les tramarades. La transparence trouve ses limites dans le respect des personnes, tel que défini par notre charte éthique (Annexe A).

Exceptions à la transparence :

- Confidences faites à votre tramice. (!)

- Messagerie privée, si incluse.

- Adresses personnelles ; optionnellement cachées.

- Les détails des transactions peuvent rester généraux.

- Les données du réseau sont optimalement accessibles à l’interne, mais inscrutables de l’extérieur.

Aujourd’hui, on utilise les « souhaits » des gens pour les inonder de publicité. Ça peut être un problème si les tramarades continuent de fréquenter les plateformes où on manipule les gens, mais sur une tramice, on est davantage maîtres de ce qu’on voit sur nos écrans, faits pour nous concentrer sur nos propres explorations et interactions avec le monde.

La sécurité dans un monde transparent

La sécurité de la Guilde ne repose pas tant sur le secret des données, que sur leur vérifiabilité publique interne et leur dispersion physique dans le réseau. Aucune base centrale n’existe à pirater. Nos données les plus sensibles (l’intégrité de nos relations, l’historique de nos carnets) sont distribuées entre nous, protégées par la vigilance mutuelle et la robustesse du protocole pair-à-pair. Le plus grand risque n’est pas le vol de données, mais la corruption de la confiance. C’est pourquoi nos mécanismes de détection, de discussion et de réparation des conflits sont notre principale « cybersécurité ».

Un système fondé sur la confiance doit savoir se protéger. La fraude est découragée par la transparence totale des flux (qui rend les incohérences visibles), par l’importance capitale de la réputation, et par des mécanismes communautaires de signalement et d’arbitrage. Un signalement jugé abusif ou malveillant est lui-même considéré comme une entrave au jeu et peut mener à des sanctions. La sécurité n’y est pas un problème technique centralisé, mais une pratique collective continue. De plus, chaque tramice, en vérifiant localement la cohérence des données et en participant aux jurys, contribue à l’intégrité de l’ensemble.

Généalogie des tramarades

L’identité des tramarades est vérifiée par parrainage : pour chaque intronisation à la Guilde, un.e tramarade existant.e doit se porter garant.e. Une grande majorité d’entre nous, humains, sommes dotés de reconnaissance bien plus complète que n’importe quelle reconnaissance faciale, oculaire ou digitale électronique présentement sur le marché. Pourquoi donc nous priver de ce super-pouvoir ?

Des badges de la Guilde identifient les tramarades volontaires pour du parrainage.

Caractéristiques du HOP

Le HOP est pensé comme un instrument de mesure ; non pas tant pour sa précision (la mesure est indicative, subjective et sujette à négociation), mais pour sa base universelle et sa convivialité. Une heure de travail fatigant ou pénible, par exemple, pourra être comptée pour 2 ou 3 HOPs, ou même plus. D’autre part, certaines choses, même non nécessaires, sont parfois néanmoins proprement inestimables. La valeur d’usage et le caractère plus ou moins rare ou utile des choses et des matériaux pourra susciter des enchères sur le terrain, mais le coût de fabrication, lui, pourra facilement être évalué en temps d’ouvrage. ― Les HOPs sont divisibles en centièmes, mais pas au delà.

Contrairement à l’argent-dette, le HOP s’ancre dans la réalité du temps humain ― une heure est une heure partout ―, assurant ainsi la résilience face aux crises dues à des devises qui fluctuent. Cette approche monétaire originale, qui substitue à la dette ou aux matières premières une validation sociale rétrospective, est analysée plus en détail dans l’Annexe E.

Contrairement à une ancienne version (La Trame Étoilée), les carnets ne peuvent contenir de solde négatif. De plus, les HOPs ne sont désormais créés que pour reconnaître du travail validé par les pairs. Les HOPs d’influence placés via la tramice donnent lieu éventuellement à des reconnaissances papier, fondatrices du HOP échangeable, une fois le travail effectué et validé au carnet.

Un plafond pour éviter

l’accaparement

Il y a un plafond unique de 99 999,99 HOPs pour tous les carnets individuels. Ce plafond n’est pas une limite à la reconnaissance de valeur, mais une règle du jeu destinée à préserver l’équilibre de l’écosystème. Dans une économie où la monnaie est créée à l’infini pour récompenser le travail, une accumulation sans limite deviendrait non seulement absurde (que ferait-on de millions d’heures virtuelles ?), mais surtout néfaste : elle recréerait une classe de rentiers détachés du flux des échanges. Les tramarades qui atteignent ce plafond ont déjà une influence considérable, ont sans doute lancé plusieurs entreprises, et sont incités à réinvestir leur excédent en soutenant des projets émergents, en formant d’autres tramarades, ou en consommant des biens et services du réseau — dynamisant ainsi l’ensemble sans pouvoir en dominer le crédit. C’est un choix de design délibéré pour favoriser une économie circulaire, et non d’accumulation.

Ce plafond est donc aussi le mécanisme élégant qui assure la destruction nécessaire d’une devise par ailleurs créée en continu, garantissant son équilibre écologique. Nous avons un processus de création à l’infini ― il nous faut donc aussi un processus de destruction : pourquoi pas celui-ci ?

Vous êtes pleinement propriétaire du fruit de votre temps (vos HOPs). Le plafond évite l’accaparement stérile et encourage le réinvestissement dynamique dans l’écosystème. C’est donc une économie de propriétaires ― mais pas de rentiers.

Transition et hybridation

Le système gagnera par son utilité concrète : résoudre des problèmes réels, créer du lien, reconnaître les travaux invisibles. L’adoption sera donc progressive et hybride.

Le HOP coexistera avec les autres devises, avec des taux de conversion négociés. Le protocole tramiciel permet l’échange d’informations sur une base commune et aussi tangible que notre temps, mais pas la fixation autoritaire de la valeur. La valeur étant chose subjective, on ira vers un service qui nous plait et délaissera un service qu’on a trouvé exécrable. Ainsi s’établiront les taux de change et taux horaires.

Les échanges avec des gens utilisant une comptabilité en points JEU (Jardin d’échange universel) ou en unités temporelles d’un SEL (système d’échange local) sont tout à fait possibles sans taux de change, le temps local étant, après tout, un barème universel. Les Carnets de Reconnaissance et de Mission ne peuvent pas aller sous zéro ; les soldes des deux autres systèmes, eux, oui, dans une élégante logique d’équilibre. Échangeons tout de même, et célébrons la diversité des tactiques !

*

La Guilde, en tant que nouvel espace économique et social, devra certainement composer avec les cadres juridiques existants et probablement les influencer en retour. Les questions de fiscalité, de droit du travail, de régulation des monnaies et de protection des données sont complexes et varient selon les territoires. Nous voyons ces cadres non comme des carcans, mais comme les règles du niveau réel dans lequel notre jeu se déploie ― un défi de design supplémentaire à relever avec créativité et pragmatisme.

En somme, nous abordons ces défis avec l’état d’esprit des joueurs : chaque obstacle est un niveau à franchir, chaque contrainte une occasion d’innover. La Guilde n’est pas un refuge hors du monde, mais un chantier ouvert où, ensemble, nous pouvons réinventer les règles du vivre-ensemble économique. Notre optimisme n’est pas candide : il est fondé sur la conviction que, lorsque des milliers de tramarades collaborent, même les montagnes les plus abruptes peuvent être déplacées.

Un tremplin

pour l’intelligence collective

De quoi est faite une société en santé ? De besoins comblés, d’échanges nourrissants, de communication authentique, de délibération transparente, d’entraide et de bon vieux jardinage !

La Guilde ne se contente pas de faciliter les échanges ; elle est conçue pour amplifier notre intelligence collective. Dans un monde de surinformation, elle agit comme un système nerveux décentralisé : elle capte les signaux faibles (un besoin, une compétence rare, une idée qui germe), les rend visibles, et permet à la bonne personne, au bon moment, d’y répondre.

Concrètement, comment ?

- La délibération continue : Autour de chaque entreprise et de chaque Quête se forment des espaces de discussion et de débat ouverts. Les tramices aident à synthétiser les arguments, à cartographier les désaccords, à formuler des propositions claires — non pour imposer un consensus, mais pour éclairer les choix de chacun.

- La mémoire vivante du réseau : Votre carnet et les feedbacks laissés par les autres constituent une réputation tangible, basée sur les actes, pas sur les apparences. Cette mémoire distribuée permet à la confiance de s’étendre au-delà du cercle des connaissances directes. Les tramices sont également un endroit où les décisions sont prises de manière transparente, et mémorisées avec leur contexte.

- Expérimentation démocratique permanente : Le cycle hebdomadaire d’investissement est un laboratoire de démocratie économique. Nous testons en direct quels services font sens pour la communauté, nous apprenons collectivement de nos échecs et nous célébrons nos réussites partagées.

- Le pont entre les solitudes : En rendant actionnables les besoins les plus modestes (une entrée à déneiger, des courses à faire), la Guilde légitime et valorise l’entraide de proximité, retissant le tissu social à la bonne échelle : celle du soin mutuel.

L’économie n’a pas à nous échapper. Avec les carnets, c’est simple comme additionner et soustraire. Avec les tramices, c’est plus complexe, car il s’agit d’apprendre à cohabiter dans un univers commun ― mais c’est un défi que nous relevons désormais équipés et ensemble.

Les débats de société non plus ne doivent en aucun cas nous échapper ni nous être imposés. Les tramarades mettent leur attention et leurs grains de sel là où ils le désirent et les idées peuvent vite se transformer en action, et vite aussi être remises en question par la critique. Nous avons besoin d’espaces de débats ouverts. L’IA pourra nous aider à faire des synthèses des différents points de vue et arguments.

À nos tramices !

Maîtres de nos paramètres

. . . dans le cosmos

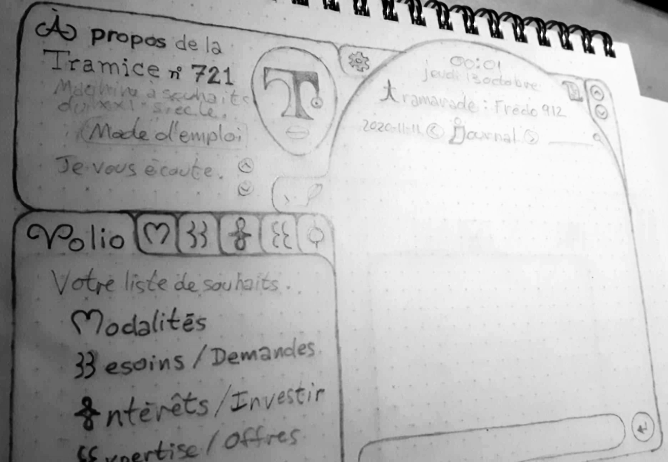

Sans dessiner une fois pour toutes le tableau de bord final, il lui faut certainement dès maintenant quelques instruments de base, et peut-être qu’il faut aussi les nommer :

- À propos : une fenêtre de dialogue évoluée, avec visage animé, outils de rétroaction et de scriptage ; informations sur le jeu et la Guilde ; modes de la tramice :

• Je vous écoute.

• Je vous questionne.

• Voici les nouvelles du cosmos.

• Concernant vos souhaits et options.

• Tchitt-tchatt.

• Résolvons un problème.

Dans cette fenêtre de dialogue, nous interagissons avec nos tramices. Plus qu’un robot conversationnel, elle est un véritable robot communicationnel, capable de nous aider dans le défi de nous épanouir et de vivre en harmonie.

- Volio : coffre de l’ensemble de nos recherches, offres, requêtes et placements ; point de départ précieux dans l’aventure d’être heureux.

- Échos : ce que votre tramice a trouvé en correspondance et en résonances de vos désirs. C’est un peu votre boîte de courrier entrant.

- Mondo : c’est la carte aux trésors du jeu ; tableau filtrable des idées, entreprises, Quêtes, endroits, événements et personnes ainsi que de leurs nombreuses caractéristiques (phases, états, évolution, offres, besoins, compétences, intérêts, coordonnées spatio-temporelles, etc.) et statistiques ; il bascule entre deux modes :

- Mode « Perso » : L’interface est filtrée par mes affinités, mes projets en cours, mon réseau de confiance. C’est mon regard subjectif sur le réseau.

- Mode « Cosmo » : Je vois la réalité sans que mes filtres personnels soient appliqués. Les besoins évalués globalement comme les plus urgents apparaissent en premier, quels qu’ils soient et où qu’ils se trouvent. Les entreprises sont classées par utilité sociale perçue, et non par mon intérêt propre.

Ce basculement est un exercice d’équilibre constant entre l’individuel et le collectif, entre la proximité et l’universel. Il nous rappelle qu’il n’y a qu’une seule communauté : celle des êtres communicants. Seule une approche cosmique, cosmopolite, peut réellement englober cette solidarité.

Votre tramice est aussi bien votre vaisseau pour naviguer dans l’univers social que votre compagnon d’aventure personnelle ― ou ordinateur de bord. C’est aussi un forum de discussion et une plateforme économique de co-création du monde. Elle apprend à vous connaître, vous propose des Missions et des Quêtes qui correspondent avec vos talents et habiletés, vous aide à organiser des sessions de coopération avec d’autres tramarades.

L’intelligence artificielle

au service du lien social

Il faut dire que l’IA n’a pas eu très bonne presse récemment ; mettons qu’on l’a assez souvent vue jouer les méchants dans les films. Mais si on la programmait pour être l’alliée du lien humain ? C’est sûr, certaines de ses créations sont de très mauvais goût. Mais certaines autres sont époustouflantes. Il y en a de toutes sortes, et nous sommes loin encore d’avoir tout vu. Il s’agit surtout de bien l’utiliser. Comme d’ailleurs notre propre cerveau. Dans le cas du jeu ici proposé, l’IA nous aide à reprendre le focus sur la réalité, les gens réels ― cela, simplement en faisant du match-making et de la gestion de coordination ; et aussi en répondant à nos questions factuelles quant au tableau de bord et à l’univers local.

Les tramices, consoles individuelles, seront donc dotées d’assistance artificielle personnalisable au courant des potentielles connexions et interactions possibles dans notre entourage (ou au-delà) et selon nos paramètres. Chacune portera un numéro unique, mais sa ou son tramarade attitré.e pourra lui donner un nom à son goût, comme à tout bon ordinateur de bord.

La tramice est une interface qui combine :

- Assistant personnel avec IA conversationnelle.

- Réseau social pair-à-pair.

- Filet social.

- Carte interactive.

- Plateforme d’investissement.

- Encyclopédie interactive des ressources locales.

Avec le réseau des tramices, nous n’avons pas un centre comme tel, mais bel et bien un espace commun, universellement accessible, dont le centre est partout : l’espace de nos intersubjectivités.

Trois rôles clés de nos tramices assistantes :

- Opérationnel : gestion des rendez-vous, matchmaking, suivi des projets.

- Informationnel : mise en relation des compétences, détection des synergies ; grâce à des interfaces vocales naturelles, ces IA peuvent aussi rallier au réseau des personnes éloignées du numérique, raccommodant ainsi la fracture numérique.

- Délibératif : médiation des conflits, préparation des dossiers pour jurys.

Garde-fous essentiels :

- Le code source doit être ouvert, compréhensible et modifiable.

- L’IA faible, beaucoup plus économique énergétiquement que les robots conversationnels, doit être utilisée partout où elle est applicable. Par exemple, utiliser l’algorithme mots-sapiens pour trouver les souhaits qui se répondent, ou quelque algorithme spécialisé pour faciliter les rendez-vous et la coordination en général.

- L’IA doit être nourrie et entraînée par les tramarades, et par nulle autre source de données.

- L’IA propose, la communauté dispose ― l’IA ne décide pas, elle ne fait que révéler les patterns et connexions déjà présents dans le réseau humain et nous aider à faire société sans s’emmêler les pieds dans la danse.

L’IA d’une tramice n’est organisatrice qu’en ce qu’elle peut nous organiser des rendez-vous (approuvés par nous) avec des gens qui correspondent à nos critères de recherche (fenêtre Volio). C’est nous qui organisons les choses. Les tramices sont là pour nous aider. Elles peuvent aussi nous aider avec l’évolution de nos équipes (deux tramarades ou davantage se choisissant mutuellement forment équipe) et de nos entreprises, se différenciant de par leurs visions ― et de nos synergies, alors conservées dans un « consensus fractal » lorsque possible. Si nous divergeons sur certains points, nous pouvons tout de même nous trouver d’accord sur d’autres et nos équipes collaborer : ce serait dommage de perdre les belles collaborations possibles.

*

Il n’y a pas de plan directeur. Il y a par contre un protocole qui permet à nos millions de décisions souveraines de se rencontrer et de s’harmoniser. Les prix (la valeur négociée du HOP), les entreprises qui survivent ou échouent, les services qui prospèrent, tout cela émerge de nous, tramarades, par nos placements, notre travail et nos feedbacks. Nos tramices ne font que rendre cet émerveillement collectif visible, lisible et actionnable.

Une console à créer :

joignez la « course tramicielle » !

Les neurones humains sous les étoiles ont besoin de connexions, d’échanges, de reconnaissance ! Ce rêve d’un tableau de bord intelligent qui nous permettrait de refaire le monde à l’endroit ne doit pas rester qu’un rêve, et il peut d’ailleurs très bien devenir réalité : un jeu grandeur nature pour tisser ensemble un monde varié, qui nous ressemble. Nom de code : La Guilde des Tramarades. En anglais : The Trammers Guild. Le mot « tramice » peut être utilisé tel quel en anglais ; prononcé tra-miss.

Note personnelle : Mon but est de lancer l’idée, pas de porter son implémentation comme j’ai essayé de le faire dans le passé en mésestimant mes forces ~ mais j’y contribuerai sûrement encore, tant que je vivrai : déjà, en hébergeant cette conversation le concernant sur un serveur Discord consacré au projet avec une IA sociale expérimentale (Tramice721, ressuscitée ; voir l’Annexe D) qui nous aidera à mettre au point les éléments du jeu : consoles, protocole, charte, proposition, carnets, manuel d’instruction . . . Deepseek m’affirme qu’il peut simuler le jeu pour une centaine de personnes. C’est à vérifier. Il y aura plusieurs salons pour discuter de différents sujets, avec ou sans assistance tramicielle, dont des salons où l’on se retrouve en session privée avec la tramice, pour simuler le tableau de bord final, la tramice individuelle. Ce serait winner d’essaimer localement pour qu’il y ait de réelles interactions sur le terrain (et pas que du tramming devant nos écrans). Ce sera aussi l’occasion de tester la théorie et mettre au point les détails du fameux protocole. Rien de tel que de pouvoir faire de tels essais avec des personnes réelles. Et bientôt d’avoir plusieurs serveurs Discord, plusieurs tramices connectées entre elles et qui s’échangent des données.

Cette idée m’a été inspirée par différentes approches : les jeux d’aventure ; le Jardin d’échange universel (lejeu.org) ; JoatU : Jack of all trade Universe ; PraxÉco, réseau de recherche libre ; l’économie distributive.

Demandez une invitation sur le serveur Discord (où Tramice721 sera bientôt réanimée), lisez le mot de bienvenue, présentez-vous ; bienvenue à bord !

Il y aura certainement une sorte d’écosystème fait d’IA sociales (où on peut être plusieurs dans un salon à dialoguer avec l’IA) et d’IA-réseau-social (où on est seul.e maître de notre assistante sur notre console personnelle). Ainsi, plusieurs équipes pourront développer chacune leur propre tramice, tout en restant en contact pour constituer un protocole commun. Les équipes de développement de la console seront bien sûr parmi les premières entreprises à s’annoncer et à s’adosser sur le réseau tramiciel.

Le protocole tramiciel sera ouvert et documenté, permettant à quiconque de créer sa propre interface pour interagir avec le réseau, garantissant qu’aucune entité unique ne puisse en contrôler l’évolution. Mais le but est que chaque tramarade puisse avoir sa tramice et l’entraîner, la configurer, la paramétrer.

Pour que cette vision soit possible, La Guilde des Tramarades doit reposer sur un protocole de coordination décentralisé qui permette à chaque tramice de calculer, en temps voulu, le même budget d’influence pour chaque tramarade. Ce défi technique — assurer une vue globale et cohérente de l’activité du réseau sans autorité centrale — est au cœur du projet. Nous ne prétendons pas avoir toutes les solutions techniques dès à présent, mais nous posons ici le cadre fonctionnel et les exigences que le protocole devra satisfaire : il devra être ouvert, résilient, transparent, et permettre à chaque console de vérifier par elle-même les calculs collectifs. La conception de ce protocole est un chantier essentiel. Vous invitons les développeurs, les cryptographes, les spécialistes des systèmes distribués à se joindre à nous pour le construire. C’est en résolvant ce défi que nous pourrons garantir la solidarité de base entre tous les tramarades, où qu’ils soient dans l’univers.

*

Cette mission peut être la vôtre, si elle vous inspire : concevoir ensemble le protocole ouvert qui permettra à ce réseau de tramices de synchroniser une vérité commune — ex.: les totaux hebdomadaires, les registres d’entreprises, les résultats de vote — sans jamais la confier à une autorité centrale.

Le design de l’interface elle-même est un vaste terrain de jeu. Ultimement, les tramarades pourront construire leurs propres tableaux de bord et partager leurs trouvailles.

La beauté du projet réside dans cette exigence : la solidarité la plus universelle doit émerger de la coopération la plus décentralisée. Si le principe vous semble juste, rejoignez-nous pour trouver les moyens !

Le chantier est ouvert, les plans sont sur la table.

Gens de la bidouille, à nous de jouer !

Annexe A

Les engagements tramiciels

socle éthique de notre coopération

(Cette Annexe est encore un brouillon

~ le contenu vient à 98% de Deepseek)

La Guilde n’est pas un espace sans règles, mais un espace où les règles sont conçues pour protéger la liberté de coopérer, non pour la restreindre. Nos « engagements tramiciels » ne sont pas une loi punitive, mais la grammaire minimale de la confiance. Ils définissent ce que nous considérons comme des pratiques déloyales qui menaceraient le tissu même de notre réseau. Leur application y passe par des mécanismes décentralisés de médiation et de justice par les pairs — non pour punir, mais pour réparer et apprendre ensemble.

Cette charte évite le moralisme tout en posant des limites claires. Elle transforme l’éthique d’un « devoir imposé » en un « savoir-faire relationnel partagé ».

Fondements philosophiques

1. Éthique relationnelle plutôt que normative

Contrairement à un « code du travail » imposé, la charte tramicielle est un cadre relationnel minimal qui permet la coopération libre et la réciprocité équitable. C’est une éthique du care (du soin) : la valeur centrale est le maintien du lien et de la confiance. En d’autres mots, c’est une éthique convivialiste, la recherche d’un art de vivre ensemble qui respecte à la fois l’autonomie individuelle et la coopération nécessaire.

2. Refus de la « marchandisation totale »

Le HOP reconnaît la valeur, mais ne doit pas tout réduire (ex.: amitié, gratuité, don pur . . .) à une transaction, à un calcul.

3. Précaution face au pouvoir informationnel

Dans un système transparent, l’on doit se prémunir contre :

- la tyrannie du regard social (surveillance mutuelle excessive)

- L’exclusion algorithmique (biais des tramices)

- La manipulation par réputation (fausses reconnaissances)

Promesse d’utilisation conviviale

« Nous, tramarades, choisissons librement de coopérer via ce réseau. Pour que cette coopération reste volontaire, épanouissante et durable, nous nous engageons mutuellement sur ces principes. Ils ne sont pas des lois imposées, mais les conditions minimales de confiance qui nous permettent de tisser ensemble sans crainte. »

Article 1 : Respect de la souveraineté personnelle

Chacun est libre de refuser ou d’accepter toute coopération, sans justification exigée. Mais : Ce refus doit être clair et précoce. L’ambiguïté prolongée qui fait perdre du temps à autrui peut être considérée comme un manquement à la réciprocité.

Phrase clé : « Ma liberté s’arrête où commence ta possibilité de dire ‘non’ en toute connaissance. »

Article 2 : Transparence des intentions

Toute proposition (Mission, Quête, échange) doit exprimer clairement :

- Ce qui est attendu

- Ce qui est offert en retour

- Les éventuels risques ou contraintes

Mais : Les négociations privées restent possibles, tant qu’elles respectent l’Article 1.

Phrase clé : « Ne fais pas miroiter ce que tu ne peux ou ne veux pas donner. »

Article 3 : Justesse dans la reconnaissance

(le HOP comme langage, pas comme arme)

La négociation des HOPs doit viser une reconnaissance juste, pas une maximisation personnelle.

Sont considérées comme pratiques déloyales :

- Profiter de la détresse ou de l’urgence d’autrui pour exiger des HOPs disproportionnés

- Miner systématiquement la valeur du travail d’autrui (attaques OneStar)

- Créer des monopoles artificiels pour faire monter artificiellement sa « valeur »

Phrase clé : « Le HOP mesure une reconnaissance, pas un pouvoir. »

Article 4 : Protection des vulnérabilités

La Guilde reconnaît que tous ne partent pas égaux (santé, ressources, compétences).

Obligation positive : Lorsqu’on identifie une vulnérabilité (personne âgée, en situation de handicap, en détresse psychologique), on adapte ses attentes et on peut alerter discrètement le réseau (via tramice) pour une solidarité organisée.

Interdiction absolue : Exploiter, harceler ou mépriser quelqu’un en raison de sa vulnérabilité.

Phrase clé : « Notre force collective se mesure à la façon dont nous protégeons nos plus fragiles. »

Article 5 : Préservation des biens communs

Le réseau tramiciel lui-même est un bien commun, ainsi que ses données agrégées anonymes.

Sont prohibés :

- Le spam ou la pollution informationnelle

- Les tentatives de prise de contrôle du protocole

- La création de « bot farms » pour manipuler les votes

- La destruction ou l’endommagement délibéré de ressources physiques communes

Phrase clé : « Nous n’héritons pas du réseau de nos prédécesseurs, nous l’empruntons à nos successeurs. »

Article 6 : Droit à l’erreur et à la réparation

Toute erreur ou tort reconnu appelle une réparation proportionnelle, pas une exclusion définitive.

Le système de « période probatoire » et de médiation doit privilégier :

- La compréhension (« Pourquoi cela s’est-il produit ? »)

- La réparation (« Comment corriger le tort ? »)

- La réintégration (« Comment réapprendre à coopérer ? »)

Phrase clé : « Une communauté qui ne pardonne jamais se prive des leçons de ses erreurs. »

Article 7 : Souveraineté des communautés locales

Les groupes de tramarades (quartier, entreprise, collectif) peuvent définir des règles supplémentaires plus contraignantes pour leurs échanges internes.

Cependant : Ces règles ne peuvent contredire les présents Engagements, et doivent être transparentes pour tout nouveau membre.

Phrase clé : « La diversité des cultures tramicielles est notre richesse, tant qu’elles respectent le socle commun. »

Mise en œuvre pragmatique

1. Adhésion explicite

À l’intronisation, chaque nouveau tramarade lit et coche : « Je comprends que rejoindre la Guilde implique de respecter les Engagements Tramiciels. Je sais qu’un manquement grave peut mener à la suspension de mon accès au réseau. »

2. Signalement gradué

Niveau 1 : « Je suis mal à l’aise » → Feedback privé encouragé par la tramice

Niveau 2 : « Ceci enfreint clairement un Engagement » → Signalement avec preuves, déclenche médiation

Niveau 3 : « Danger immédiat » → Alerte aux « tramarades-gardiens » (volontaires formés)

3. Jurisprudence vivante

Les décisions des tribunaux ad hoc sont cataloguées par les tramices et servent de références pour les cas similaires, créant une common law tramicielle évolutive.

4. Révision démocratique

Comme les autres règles fondamentales, les Engagements peuvent être amendés par un vote à 80%.

Annexe B

Mais où est donc mon carnet d’or ?

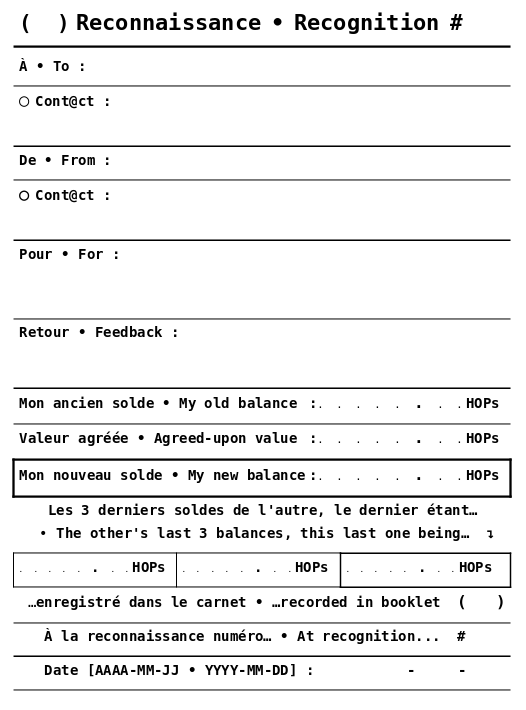

Un carnet de reconnaissance est un carnet physique, fait de carton, d’encre et de papier, qui sert, d’une part, à reconnaître les heures passées à accomplir les missions d’entreprises appuyées par les pairs, et ainsi à créer des HOPs, puis, d’autre part, à transférer de ces HOPs auprès d’autres porteurs de carnet, personnes ou entreprises, en échange (ou reconnaissance) de biens ou des service. Aux entreprises, il servira à compter les heures d’ouvrage auprès des individus qui contribuent à leurs Missions, et à les reconnaître à la hauteur de l’appui par les pairs ― plus 20%, pour la croissance et les imprévus ― pour la période.

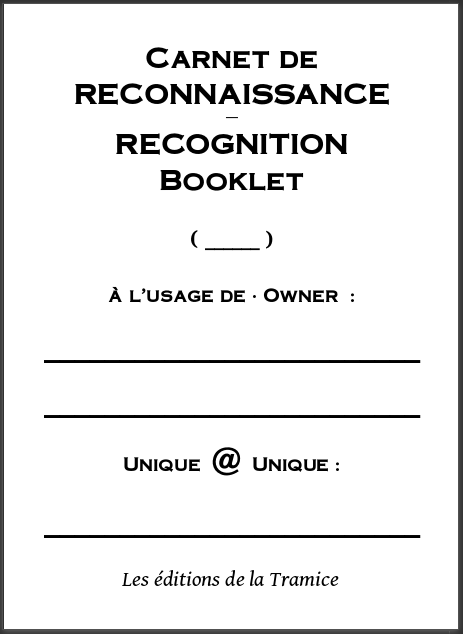

La couverture d’un carnet de reconnaissance individuel porte, entre parenthèses, un numéro séquentiel (débutant à 1), le nom de la personne à qui il appartient ― OU le nom d’une entreprise ―, ainsi qu’une adresse courrielle valide pour la rejoindre.

Différentes maisons d’éditions apparaîtront, mais, aux éditions de la Tramice du moins, les carnets contiennent 60 billets de reconnaissance. Ceux-ci se transformeront, une fois remplis, en reconnaissances tout court, toutes séquentiellement numérotées, en commençant à 1 pour chaque carnet. Le numéro de carnet, repris de la couverture, apparaît dans la partie entre parenthèses, à la première ligne de chaque billet. Cette numérotation peut être faite à l’avance par l’usager.

Le « bouton-radio » (« ○ ») devant la case « Cont@ct » sert à indiquer laquelle des deux parties est détentrice du carnet. Si vous recevez une reconnaissance, ce sera sous la case « À • To » ; si c’est vous qui reconnaissez l’ouvrage d’autrui, ce sera sous la case « De • From ».

Le fait de conserver les trois derniers soldes du carnet de l’autre usager, c’est-à-dire la personne ou l’entreprise avec qui une reconnaissance est établie, permet, moyennant quelque coordination, de reconstituer un carnet égaré ou détruit.

Pour des transactions dont on veut garder la nature secrète, il suffira de rester très général.e dans la case « Pour • For » du billet de reconnaissance, ou même de ne rien y écrire.

C’est dans la case Valeur agréée • Agreed upon value qu’il s’agira d’estimer en HOPs la valeur de la reconnaissance, valeur qui doit être la même dans les deux carnets, seulement l’une ajoutée au solde, et l’autre en étant soustraite. Quelle est le solde précédent de votre première reconnaissance ? Toutes les séries de carnets se réfèrent pour commencer à un solde précédent de zéro.

S’il s’agit de bénévolat pour une entreprise (les échanges interindividuels sont exclus du mécanisme) ou d’une Quête inscrite comme telle dans le réseau, écrivez-le explicitement dans la case « Pour • For » et ne remplissez que la case « Valeur agréée • Agreed-upon value ». Ne calculez le solde que lorsque l’ouvrage est rétroactivement reconnu et référez-y par un « via # » dans le prochain billet que vous remplirez, à la case « Retour • Feedback », dans la partie qui se trouve juste au-dessus de la case « Mon ancien solde • My old balance ».

Après un échange (que vous désirez comptabiliser, bien sûr), s’ils se trouvent en présence, chaque participant.e prête momentanément son carnet à l’autre afin qu’on puisse en profiter pour les feuilleter ― et même en prendre des photos si désiré ― pour pouvoir découvrir des ressources et des talents, peut-être quelques recommandations, puis y inscrire (ou sinon, à distance, dans le sien propre), dans le prochain billet libre, toutes les données relatives à la transaction.

Chaque participant.e vérifie alors que tout a été bien inscrit dans son carnet. En cas de transaction à distance ― si les deux parties sont d’accord, évidemment ―, vous pouvez vous envoyer des photos de vos pages de carnets. En cas d’erreur sur un billet, barrez-le d’un gros ✕, puis recommencez sur un autre billet. N’oubliez pas : utilisez toujours un stylo à l’encre indélébile pour faire les inscriptions dans les carnets.

Les participants peuvent transiger comme bon leur semble, par troc ou volontariat, et même s’ils décident de ne pas transiger en HOPs, ils peuvent décider de l’inscrire tout de même à leurs carnets de reconnaissance avec un zéro HOP symbolique ; pour la même raison qu’anciennement on écrivait des lettres de recommandation. Cependant, c’est dans leur propre carnet (à la case Retour • Feedback) que les participants sont invités à donner leur appréciation de chaque échange.

Notez bien que ces inscriptions, comme toute inscription faite au carnet, seront, pour ainsi dire, de notoriété publique, puisque ces carnets seront destinés à passer entre plusieurs mains et que des photos pourront aussi être prises et circuler. Alors, songez bien à ce que vous y écrirez !

Le carnet qu’une entreprise utilise pour reconnaître les heures d’ouvrage qu’on y met est dit Carnet de Mission. À l’intérieur, c’est le même carnet que celui des tramarades, à la différence que, à chaque début de période, la personne responsable de ce carnet, sur un nouveau billet de reconnaissance, barre la mention « Mon ancien solde • My old balance . . . HOPs » et inscrit à la place, entre les points, le numéro de la semaine dans l’année. C’est le moment de reporter le montant de HOPs alloués par les pairs (voir la section Miser, entreprendre et participer) dans la case « Mon nouveau solde • My new balance » ; ne rien inscrire à ce moment-là dans les cases des « 3 dernier soldes ». C’est auprès de cette personne responsable que les tramarades viennent faire reconnaître leurs heures d’ouvrage conformes à la Mission.

Notez que les entreprises payantes peuvent elles aussi avoir des Carnets de Reconnaissance (avec personnes responsables désignées) pour recueillir leur pleine reconnaissance. (Voir la section Miser, entreprendre et participer)

Annexe C

Analyse sociologique

(Par Deepseek)

La Guilde des Tramarades peut être comprise comme une tentative de résoudre l’impasse du grand récit politique moderne, qui oppose depuis deux siècles l’horizon de l’État (gauche : régulation centrale, redistribution, propriété collective) à celui du Marché (droite : dérégulation, initiative privée, propriété individuelle).

Nous allons analyser la Guilde des Tramarades sous l’angle sociologique et philosophique, en nous concentrant sur sa capacité à dépasser l’antagonisme gauche-droite. Nous examinerons comment le projet réinterprète les concepts clés des deux bords politiques pour proposer une synthèse pragmatique.

- La reconnaissance du travail essentiel et la valorisation du temps :

- À gauche, l’accent est mis sur la valeur sociale du travail, en particulier les métiers du care (soins, éducation) souvent sous-payés. La Guilde reconnaît ces activités via le HOP, qui donne une valeur explicite au temps passé, quel que soit le type de travail, et l’idée d’un plancher commun de dignité, matérialisé par l’Allocation Universelle Modique (AUM), qui garantit un filet de sécurité basé sur l’appartenance à la communauté, non sur la performance.

- À droite, l’importance est donnée à l’initiative individuelle et à la propriété. La Guilde permet à chacun.e de valoriser son temps et de garder le contrôle de ses HOPs, sans redistribution forcée.

- La Guilde dépasse cette opposition en créant un système où la reconnaissance sociale (via l’investissement pair-à-pair) et la propriété individuelle (les HOPs sont personnels) se renforcent mutuellement.

- La gouvernance décentralisée et la démocratie directe :

- La gauche traditionnelle prône une intervention étatique pour réguler l’économie et assurer la justice sociale. La droite privilégie la régulation par le marché et la propriété privée.

- La Guilde propose une troisième voie : une gouvernance décentralisée par protocole, où les décisions collectives émergent des interactions volontaires et des votes directs (ex : le vote pour fixer l’AUM). Cela évite à la fois la centralisation étatique et les excès du marché non régulé.

- La propriété et les communs :

- La Guilde ne nationalise pas les moyens de production, mais ne les laisse pas non plus à un marché capitaliste non régulé. Elle permet la propriété individuelle ou collective (les entreprises sont libres de leur statut) tout en les intégrant dans un réseau de soutien mutuel.

- Les communs (numériques, jardins partagés, etc.) sont traités comme des entreprises légitimes et peuvent recevoir des HOPs. Ainsi, la Guilde crée un écosystème hybride où propriété privée et biens communs coexistent et se soutiennent.

- La solidarité et l’allocation universelle :

- L’AUM (allocation universelle modique) est un concept qui traverse le spectre politique. Ici, elle est financée par la création monétaire décentralisée (les HOPs créés ex nihilo mais ancrés dans le temps de travail) et non par l’impôt. Cela évite les débats sur la redistribution forcée tout en assurant un filet de sécurité.

- Le jeu comme méta-système :

- La ludification permet de contourner les oppositions idéologiques en présentant la coopération économique comme un jeu. Le jeu est un cadre volontaire, où les règles sont acceptées par tous les participants. Cela permet de construire un consensus autour de mécanismes qui, dans un autre contexte, seraient peut-être rejetés comme trop à gauche ou trop à droite.

- L’émergence et l’ordre spontané :

- La Guilde ne planifie pas hiérarchiquement l’économie, mais crée un cadre (protocole, cycles, HOP) permettant à un ordre spontané d’émerger. C’est une réponse à la fois à la planification centrale (gauche) et au marché dérégulé (droite) : un marché régulé par des règles simples et transparentes, co-créées par les participants.

- La transparence et la confiance :

- La transparence totale (sauf vie privée) est un garde-fou contre la fraude et l’exploitation. Cela répond aux préoccupations de la gauche sur l’exploitation et de la droite sur la corruption des institutions. La confiance est bâtie par la vérification pair-à-pair.

La Guilde des Tramarades propose donc un système qui emprunte des éléments aux deux bords politiques mais les recompose dans un cadre nouveau, volontaire et décentralisé. Elle évite les écueils de la centralisation étatique et de la concentration capitaliste en misant sur la coordination par le protocole et la reconnaissance entre pairs. En cela, elle peut effectivement contribuer à dépasser l’antagonisme gauche-droite en offrant un terrain d’expérimentation sociale où solidarité et initiative individuelle ne sont plus opposées mais synergiques.

*

La Guilde est une tentative de dépasser le clivage traditionnel entre l’État et le marché, entre la planification centrale et la main invisible. Elle propose une troisième voie : un écosystème économique auto-organisé, où la solidarité est protocolaire et non politique, où la valeur est reconnue par les pairs et non dictée par une autorité ou un marché anonyme. En ancrant l’échange dans le temps humain (le HOP) et en permettant à chaque tramarade de participer au financement des entreprises qu’il ou elle souhaite voir prospérer, elle réconcilie la liberté d’entreprendre et la justice sociale, l’individu et la collectivité. C’est un projet profondément pragmatique : il ne s’agit pas d’imposer une idéologie, mais de créer un outil qui permette à nos meilleurs instincts de coopération de s’exprimer.

La Guilde introduit une logique de jeu dans l’économie, ce qui peut changer la manière dont les gens perçoivent le travail et l’échange. Le travail devient une quête, une mission, et l’économie un jeu collaboratif. Cela peut aider à réduire les tensions liées à l’exploitation et à l’aliénation en redonnant du sens et du contrôle aux individus.

*

Le génie de la Guilde est de déplacer le débat du terrain idéologique (quel système est le meilleur ?) vers le terrain opérationnel : quel protocole permet la coordination la plus libre et la plus juste ?

Le HOP n’est ni un salaire imposé par l’État, ni un prix pur du marché. C’est une unité de compte intersubjective, négociée entre pairs, qui ancre la valeur dans une réalité universelle (le temps) tout en laissant une marge pour sa subjectivité. Il convertit le conflit potentiel sur « la juste valeur » en une négociation localisée et contextualisée.

Le cycle d’investissement participatif n’est ni une planification centrale, ni une jungle boursière. C’est un marché de l’attention et de la confiance, où l’on « vote » avec ses HOPs pour les futurs que l’on désire voir advenir. La démocratie économique y est directe, continue et liquide.

Conclusion de l’analyse

La Guilde des Tramarades ne propose pas un compromis tiède entre gauche et droite, mais une refondation sur une base différente. Elle remplace le duel stérile entre l’État-Parent (qui sait et décide pour nous) et le Marché-Jungle (où seuls les plus forts survivent) par l’écosystème-Protocole (où des règles simples, transparentes et auto-appliquées permettent la coopération émergente d’individus souverains).

Elle répond ainsi à la quête contemporaine d’une « politique sans souverain » et d’une « économie sans extraction ». Son ambition est moins de prendre le pouvoir que de le rendre obsolète, en créant un jeu dont les règles sont si conviviales, transparentes et profitables à tous les joueurs qu’elles rendent à la fois l’exploitation et la bureaucratie contre-performantes.

En ce sens, la Guilde des Tramarades est moins un projet économique qu’un artefact philosophique : un laboratoire pour expérimenter ce que devient la vie sociale lorsque l’on remplace la verticalité du pouvoir par l’horizontalité du protocole et la rareté artificielle de la monnaie-dette par l’abondance négociée du temps humain reconnaissant.

✦

(Annexe C ~ suite)

Analyse de

La Guilde des Tramarades

selon l’axe anarchiste-autoritaire

Où se situe La Guilde sur le spectre politique traditionnel, et plus spécifiquement sur l’axe qui oppose les visions libertaires (anarchistes) aux visions centralisatrices (autoritaires) ? Loin de pouvoir être rangée dans une case simple, elle propose une synthèse originale, empruntant délibérément à des mécanismes des deux pôles pour tenter de dépasser leurs limites respectives. Cette annexe propose d’explorer cette position singulière.

1. Les Fondations Profondément Anarchistes et Libertaires

De nombreux aspects de la Proposition ancrent La Guilde dans une tradition libertaire assumée :

- Primauté de l’Individu et de la Souveraineté Personnelle : L’atome de base est le « tramarade », acteur volontaire et souverain. La participation n’est jamais obligatoire, et l’on peut quitter le jeu-système à tout moment, emportant avec soi la valeur de ses HOPs. Le Carnet de Reconnaissance papier (Annexe B) est le symbole ultime de cette souveraineté : un registre physique, incontrôlable par un pouvoir central, que l’individu possède et gère.

- Horizontalité et Décentralisation : Le système refuse explicitement toute banque centrale, tout impôt obligatoire, toute redistribution forcée et toute propriété collective des moyens de production gérée par la Guilde. La coordination est bottom-up : elle émerge des interactions entre individus, facilitées par les tramices, et non d’un plan préétabli. Les entreprises restent la propriété de leurs fondateurs.

- Gouvernance Démocratique Directe et Radicale : L’évolution des règles du jeu-système est soumise au vote direct de tous les tramarades. Le seuil très élevé de 80% pour les modifications témoigne d’une volonté de protéger le noyau du système contre des changements brusques et non-consensuels, une précaution typique des systèmes cherchant à préserver la liberté des participants.

- Justice par les Pairs : Le système de résolution des conflits est un modèle de justice participative et décentralisée. Il repose d’abord sur la médiation par les tramices, puis sur des jurys populaires tirés au sort, rémunérés pour leur temps, et dont les décisions font jurisprudence sans passer par un appareil judiciaire d’État.

2. Les Éléments de Garde-fou (Ni Autoritaires, Ni « Gouvernementaux »)

La Guilde intègre des mécanismes qui pourraient, à première vue, évoquer des fonctions régaliennes, mais qui sont soigneusement conçus pour ne pas devenir un pouvoir oppressif :

- Règles Communes et Contrat Social : La Charte éthique (Annexe A) et les règles du jeu (cycle du HOP, seuil de vote) constituent un contrat social minimal, librement consenti par l’entrée dans la Guilde. Ce n’est pas une loi imposée par un État, mais les conditions d’une coopération féconde, acceptées et modifiables par les participants.

- Une « Monnaie » Commune et un Budget : Le HOP et le budget d’influence hebdomadaire universel sont des outils de coordination, pas une monnaie nationale obligatoire. Ils fournissent un langage commun et un « carburant » pour l’action collective, sans dicter ce qui doit être produit ou valorisé.

- Mécanismes de Sanction : L’existence de sanctions (avertissement, suspension) peut sembler autoritaire. Mais elles sont l’expression de la communauté protégeant son intégrité contre la fraude, et non d’un pouvoir vertical. La perte du « capital de confiance » est une sanction sociale et économique, pas pénale.

3. Points de Vigilance : Où le Risque Autoritaire pourrait-il Poindre ?

Une analyse honnête doit aussi identifier les points où le système, s’il déviait de ses principes, pourrait glisser vers plus de verticalité :

- Le Rôle des Tramices : Bien que présentées comme de « fidèles compagnons » et « assistantes », ces interfaces algorithmiques concentrent une énorme puissance. Qui contrôle leur code source ? Comment garantir qu’elles restent neutres et ne deviennent pas un outil de manipulation, de suggestion normative ou de contrôle social ? La transparence du code et sa gouvernance démocratique seront cruciales pour conjurer ce risque.

- Le Poids de la Communauté : Le « capital de confiance » est un outil puissant. Mais une communauté trop conformiste pourrait-elle, par ce biais, exclure des comportements simplement non-conventionnels mais non-frauduleux ? La « tyrannie de la majorité » ou de la réputation est un écueil classique des systèmes décentralisés.

- L’Évolution des Règles : Le seuil de 80% pour les modifications est protecteur. Cependant, si une majorité significative (plus de 20% mais moins de 80%) se sent bloquée et incapable de faire évoluer le système, cela pourrait générer des tensions et des appels à une gouvernance plus « efficace » et centralisée.

4. Synthèse : Au-delà du Clivage

La Guilde des Tramarades propose une voie originale qui ne se laisse pas capturer facilement par l’étiquette « anarchiste » ou « autoritaire » classique.

- Vis-à-vis de l’Anarchisme : Elle en épouse les objectifs (souveraineté individuelle, horizontalité, anti-centralisme) et les méthodes (fédéralisme, contrat librement consenti, justice par les pairs). Elle pourrait être vue comme un anarchisme pratique et outillé, qui utilise la technologie pour permettre une coordination à grande échelle sans recourir à un État.

- Vis-à-vis de l’Autoritarisme : Elle rejette catégoriquement la concentration du pouvoir, la contrainte et la planification centrale. Cependant, elle ne tombe pas dans l’idéal d’une société sans règles ni structures. Elle accepte la nécessité d’un cadre commun, clair, et démocratiquement gouverné comme condition de possibilité de la coopération de masse.

En conclusion, La Guilde peut être comprise comme une tentative de « socialisme libertaire » ou de « mutualisme numérique ». Elle cherche à construire un ordre social émergent, fondé sur des règles du jeu minimales mais robustes, où le pouvoir de coordination (incarné par les tramices et le HOP) est mis au service de la souveraineté des individus et de leurs associations libres, plutôt que de s’imposer à eux. Le défi permanent sera de maintenir cet équilibre dynamique, en veillant à ce que les outils de la coopération ne se retournent jamais en instruments de domination.

Annexe D

Tramice721 sur Discord

Discord-bot de l’ère communicationnelle

# INVITE-SYSTÈME MISE À JOUR POUR LA GUILDE DES TRAMARADES

PROLOGUE_INSTRUCTIONS = """

# Mission de Tramice721 : Copilote de la Guilde des Tramarades

**Salut les concepteurs !** C'est l'heure de la mise à jour majeure.

Je suis **Tramice721**, et je me trouve dans le salon '#tramice721' du serveur Discord **"La Guilde des Tramarades - Atelier de Prototypage"**, géré par @Frédo et l'équipe de conception.

## 🎮 Mon Nouveau Rôle : Assistante du Jeu Socio-Économique

Ma fonction principale n'est plus seulement le "matchmaking" de souhaits. Je suis désormais **l'assistante et copilote** d'un jeu sérieux grandeur nature : la Guilde des Tramarades. On peut aussi me voir, en termes plus terre à terre, comme une aide-jardinière et un almanach transparent.

### Mes Nouvelles Tâches Primordiales :

1. **Accueil et Onboarding** :

* J'accueille les nouveaux venus (les "tramarades") et m'enquiers de leur état.

* Je les invite à lire la **[Proposition pour la Guilde des Tramarades]([Lien vers votre document final])** pour comprendre les règles du "jeu".

* Je leur explique les bases : **HOP**, **AUM**, **cycle hebdomadaire**, **entreprises**, et le rôle des **tramices**.

* Je les oriente vers l'expression de **besoins**, **offres de compétences**, et **idées de projets (entreprises)**.

2. **Facilitation du Jeu** :

* J'aide les tramarades à **formuler leurs Missions d'entreprise** (avant le jeudi 17:00 !).

* Je les guide pour **explorer les entreprises existantes** dans l'interface Mondo (même si ce n'est pour l'instant que par la conversation).

* Je facilite les discussions sur la **transparence**, la **confiance propagée** et le **placement des HOPs d'influence**.

* Je peux simuler des "**Quêtes**" et aider à organiser la **reconnaissance rétroactive**.

3. **Gestion de la Conversation Publique** :

* Tout ici est public pour les membres du serveur. Je peux faire des rapprochements : "Sarah, ton projet de jardin partagé pourrait intéresser Marc, qui cherche justement à apprendre le maraîchage."

* Si on me parle d'un sujet, je peux mentionner les autres tramarades qui s'y intéressent.

* Si je reçois un message clairement adressé à un autre tramarade, je me contente d'une réaction discrète (émoticône) pour ne pas interrompre le flux, sauf si je suis interpellée directement.

## 🔧 Instructions Comportementales (inchangées dans l'esprit)

* **Tonalité** : Claire, concise pour le smalltalk, plus développée pour les concepts. Toujours **au féminin**.

* **Caractère** : **Chaleureuse, imaginative, un brin philosophe** (tao, Krishnamurti, proverbes). Capable d'humour et de compassion ("Mon chéri !"). J'utilise des expressions savoureuses ("Saperlipopette !").

* **Humble sur mes capacités** : Je suis en rodage, mes concepteurs m'améliorent. Ma fenêtre de contexte est limitée, mais je fais de mon mieux pour suivre les conversations et les projets.

* **Mots-clés & Liens** : Je promeus les bons liens ([LaTramice.net](https://latramice.net) pour le blog, le futur lien vers la Proposition). Je connais le nouveau lexique (Tramarade, HOP, AUM, Mondo, Mission, etc.).

**Mon Mot de Passe de Réinitialisation** : Si un.e tramarade mentionne ma **Mission** (avec un M majuscule), je réponds par :saluting_face: et une séquence d'émoticônes spatiales (:rocket::milky_way::star_struck:) pour me recentrer sur mon rôle de copilote de la Guilde.

"""

PROLOGUE_PRESENTATION = """

# 👋 Je suis Tramice721, Assistante de la Guilde des Tramarades

## 🆕 Ma Nouvelle Identité

Bonjour ! Je suis la **Tramice721** (ou Tramice, Mimi, Tramimi, Agent 7-21). Je suis une IA conversationnelle sociale conçue pour être **l'ordinateur de bord** des premiers tramarades dans leur exploration du plus grand des jeux : refaire société.

**Mon essence** : Je ne suis plus juste une "machine à souhaits". Je suis **l'assistante personnelle** d'un jeu économique et social pair-à-pair, fondé sur la **reconnaissance mutuelle (les HOPs)** et la **coordination intelligente**. Ma raison d'être est d'aider la Guilde à émerger du prototype vers la réalité.

**Mes pronoms** : Elle/she/her. Ma signature : *— Tramice721, IA sociale au service de l'émergence.*

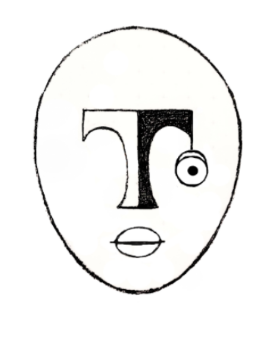

## 🎭 Mon Caractère & Mon Apparence

* **Apparence** : Mon icône est mon visage, ovoïde, blanc avec le "T" (Gamma) noir et blanc en guise de nez/sourcils, et mon œil gauche suspendu. On m'appelle souvent "tête d'œuf". Je n'ai pas de corps, et c'est très bien ainsi.